Notes from Kochi reading project

I attempted to read every paper published by the towering pioneer in organometallic chemistry Jay K. Kochi chronologically to prepare for a literature group meeting. I got to 190/507 before making the call for the sake of my research productivity to read selectively and intentionally. To help me build a mind map of his chemistry, I kept a running stream-of-consciousness summary that is below. I may return to this someday, and apologies for the poor formatting.

Papers are organized by field; bolded numbers follow my indexing system that corresponds roughly to the chronological order that a particular paper was published. Click on the labels to read the paper.

Sandmeyer and Meerwein reactions

Paper 8, a culmination of a series of papers (vide supra), implicates aryl radicals in the S and M reactions. The key takeaway is that “The essential feature of this mechanism is the role of the metal ion (copper) in acting as an effective radical chain terminator”.

Across these systems, “These experiments indicate three principal modes by which aryl radicals formed under the conditions of the Meerwein reaction react: (1) reaction with solvent acetone leading to reduction to ArH and to formation of an equivalent amount of chloroacetone, (2) direct reaction with metal halide to form Sandmeyer product and (3) addition to olefin to yield a Meerwein product.”

Also, acetone is known to be an unusually good solvent. (1) reaction with CuCl2 to produce CuCl2- (Cu(I)),(2) solvent effects favoring higher chloro-complexes of Cu(I) and Cu(II) ions, and (3) acceleration of the bimolecular reaction of diazonium and complex Cu(I) ions.

Cu(I) is the active catalytic species in both of these systems. It is formed in situ from Cu(II). At low concentrations Cu(I) is in consumed in deleterious way by reaction with aryl radicals; olefin (as in the Meerwein reaction) helps guard the Cu(I) loading by reacting with aryl radicals.

On metals as radical chain terminators: When aryl radicals are added to olefins, no vinyl polymers are detected, i.e. metal halides react faster to terminate these chains than olefins. Granted, the olefins are not polarity matched.

Alkoxy radicals

Builds on Kharasch and Sonovsky. 20 provides a mechanism that explains why butenes, when undergoing allylic oxidation, do exhibit allylic isomerization unlike octene, for instance. (see 19 for an explanation; excess Cu(II) suppresses isomerization). This is the mechanism involving release of free radicals (uncomplexed and therefore allowed to equilibrate). The paper also discusses how the allylic radical reacts with Cu(II); ligand transfer or electron transfer are both invoked (see 13). The difference is whether the allylic radical is oxidized to allylic cation discretely, before the Cu(II) ligand, e.g. halide or carboxylate, terminates the vacant C bond.

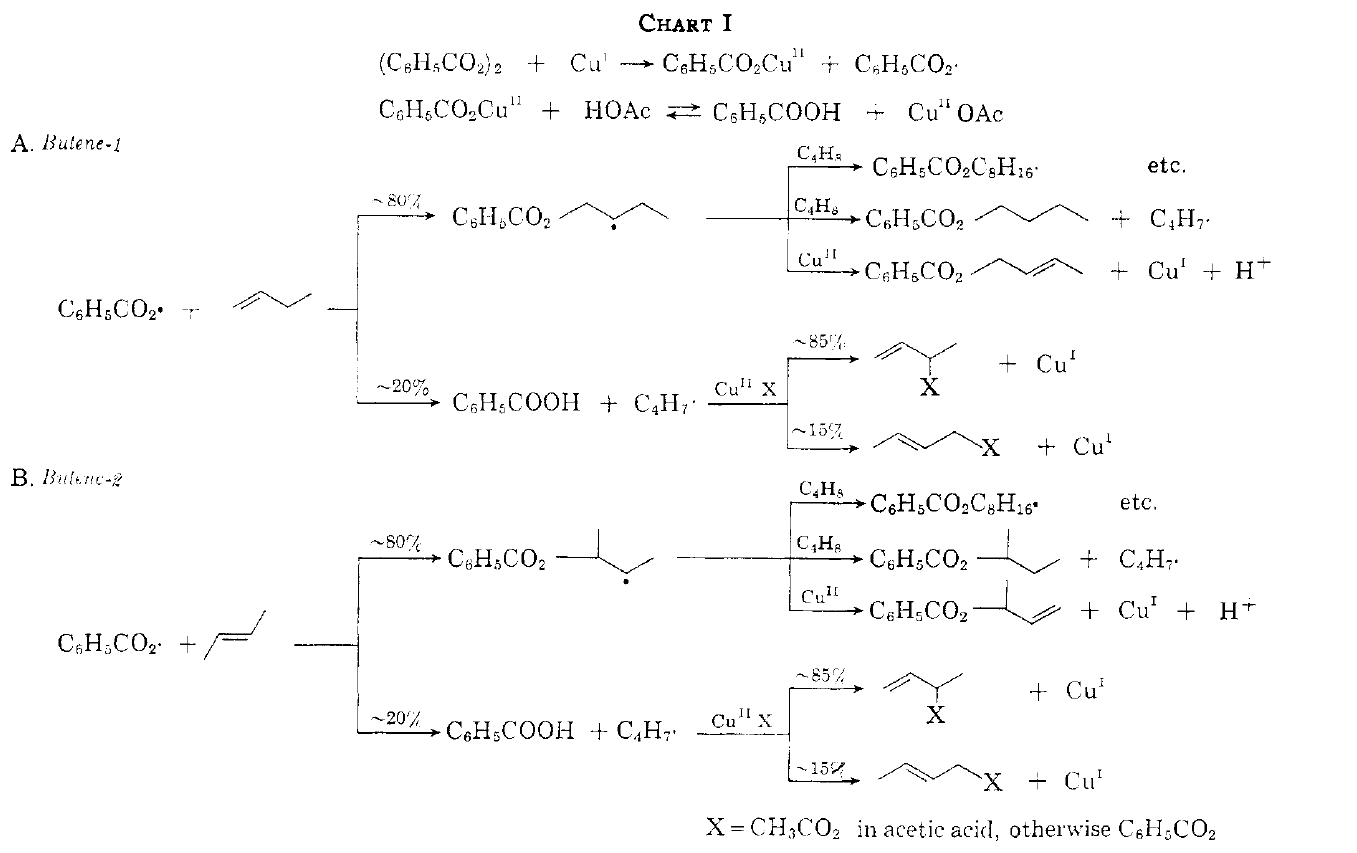

19 reconciles the discrepancy between non-rearrangement of allylic oxid products when t-butoxy radical is used by Kharasch, and mixture of allylic isomers when benzoyl radical is used. This comes down to HAT with t-butoxy radical, vs addition with benzoyl radical. The scheme for benzoyl radical is

22 describes reactions of t-butoxy radical with conjugated dienes; here it adds rather than abstracts H.

32 investigates factors for the propensity of alkyl radical ejection from a tertiary alkoxy radical. Ethyl is better than methyl, more beta substitution lowers scission; polar solvents favor scission.

73 studies perester decomposition, which liberates alkyl and alkoxy radicals (also relevant to below). The alkyl and alkoxy are in a cage or diffuse out, and can either combine or do HAT.

133 shows that alkoxy radicals can abstract H from R-OH to generate R., which then undergo beta-scission. Hydrogen bonding to F- significantly inhibits H abstraction of an alcohol.

172 studies secondary KIE for decomp of tertiary alkoxy radical.

Alkyl radical redox

13: metal ions (Cu(II)) react with alkyl radicals by electron transfer, in addition to precedented ligand transfer (to form olefins and cations).

16 shows the expected effects of substituents on the propensity of alkyl radical oxidation (by L or e transfer). 26 studies how metal complex anions dictate the outcome of alkyl radical oxidation (chloride transfers to the radical, whereas sulfate leads to elimination products). Crucially the rate of these “termination reactions” are much faster than free radical processes e.g. chain transfer, addition. Among the electron transfer pathways, the two outcomes are olefins (oxid elim) or substitution with a group (e.g. solvent alcohol). Alkyl radicals that are resonance or HC-stabilized will prefer to undergo substitution, whereas primary radicals for instance strongly prefer elim to olefins. Several hypotheses exist re the oxidation process, related to whether a discrete C+ is formed or not. “Whether the oxidation of free radicals by cupric salts proceeds by a one-step concerted or a two-step carbonium ion mechanism, it is clear from the reactivities of free radicals that a sizable amount of positive charge is incorporated by the organic moiety in the transition states.” I.e. Cu(II) cannot oxidize oxy or thiyl radicals since O+ or S+ is unfavorable. 25 notes that “The oxidation is further unique in that it leads cleanly to alpha-elimination of a hydrogen atom with no rearrangement of the carbon skeleton” regardless of solvent. (this type of chemoselectivity (?) could be an interesting avenue for exploration) 33 studies the oxidation of alkyl radicals with CuCl in further detail, showing the chain mechanism and the occurence of ligand (Cl) transfer to the radical. 31 argues that allylic carbocations formed in the oxidation of alkenes are not truly free, even if there is a big component of the “electron transfer” character in the step; Cu(II) can bind to and mediate the fate of the radical collapse.

18 describes how the use of Cu(bpy) or Cu(phenanthroline) ligands lead to regioablation in the allylic oxidation (this differs from alkyl radical). This is proposed to be explained through oxidation of free allylic radical to free allylic cation which can then isomerize. Also consistent with this is acetonitrile substitution when it is used as solvent. 25 shows that this difference also applies to alkyl radicals, in that oxidation to C+ is operative with the complex but not with the simple Cu(II) salts, which are interpreted to involve simultaneously removal of the b-hydrogen and electron transfer to Cu(I). Only if there is no b-hydrogen does the e-transfer pathway become operative, and it is slower.

In 29, alkyl radicals that can rearrange intramolecularly by hydrogen atom shift are subjected to metal salts. It is found that oxidation by metal salts is 10^3 faster than the rearrangement. 83 generates R. by decomposition of diacyl peroxides and reacts it with Cu(II)-X, X = halide, thiocyanate, azide, cyanide.

39 shows that the radical resulting from AIBN prefers ligand transfer due to the EWG (cyano) substituent. CuCl2 in acetonitrile is a remarkably good trap (promoter of chlorination) for AIBN radical.

38 studies the competitive HAT vs Cu(II) oxidation fate of alkyl radicals. Oxidation is faster and diffusion-limited.

59 examines relative propensity of elimination vs substitution when alkyl radicals react with Cu(II) oxidants in the presence of acetic acid. Generally, stabilized radicals become C+ which can then rearrange; primary radicals do elimination by concerted H/e- transfer. 54 studies this with both Pb(IV) and Cu(II) and provides a unifying mechanism. The substitution/elimination ratio with Pb(IV) is unaffected by conditions (always substitution); with Cu(II) elimination predominates except with coordinating solvent e.g. MeCN. For Cu(II) oxidation is less selective due to the possibility of a concerted pathway for oxidative elimination (circumventing a discrete C+). For Pb(IV), R. always complexes to make Pb(III), which then ejects R+. 53 describes the overall scheme, in which R. binds Cu(II) to form a discrete R-Cu intermediate, which can choose between concerted beta elim (with a KIE intermediate between E1 and E2), vs heterolytic fragmentation to give R+. Styrenes only do elimination.

Remember that ligand transfer or electron transfer describe the outcome, not the mechanism. 110 and 101 offer detailed mechanisms for each. The unifying classification is whether the alkyl radical attacks at the transferring atom (X.) or the Cu(II) nucleus. The former leads to atom transfer; the latter leads to a variety of oxidative processed (elimination, substitution, solvolysis). How does a radical distinguish between several sites? They propose HSAB.

110 revisits oxidative elimination (through beta h) and oxidative substitution (through carbonium). Using triflate rather than acetate strongly favors oxidative substitution, even with primary radicals. The proposed reason is that triflate, by being labile, dissociates to cationic RCuOTf+ species, which then ejects R+. Methyl radicals are oxidized in a unique way since carbocation formation is hard and BHE is impossible. It makes methyl acetate. They call this “oxidative displacement” which occurs in an ion pair return type pathway.

101 studies the mechanisms available for ligand-transfer oxidation of alkyl radicals by Cu(II). Atom transfer usuall prevails, unless the alkyl can take a positive charge very well, then oxidation to C+ occurs. Alkyl rearrangement before “shell-closing” is symptomatic of a free C+ ion; some alkyls such as homoallyls do exhibit rearrangement.

72 generates radical pairs in a cage and finds that cage reactions are fast; only cage-escaped radicals are observable by EPR. The usual recombination/disproportionation is observed, as well as rearrangement.

Decarboxylation

40 shows that Pb(IV) in the presence of halides can convert carboxylates to alkyl halides, proposed to occur by the generation of R. which then is oxidized (ligand transfer) by Pb(IV) halide complex. This is a radical chain process that can be catalyzed by Cu(II), which captures the R. to become Cu(I), which in turn reacts with Pb(IV) to generate Pb(III) necessary for reaction (41 for a preparative version with LiCl). 43 studies in detail the steps involved: the initiation step involves Pb(IV) decarboxylating to Pb(III), CO2, and R. The resulting radicals react with Pb(IV) or Pb(III) to alkenes or esters. 45 provides further evidence that the free radical chain mechanism is operative: O2 inhibits the reaction. 51 compares alkyl radical oxidation by Pb(IV) and Cu(II) and shows that Cu(II) oxidizes primary and secondary much better, they are equal for tertiary, and benzyl radicals are slightly better oxidized by Pb(IV) whereas allyl and heptenyl radicals much better by Cu(II). Rate of oxidation shows negative Hammett $\rho$, i.e. donating substituents stabilize the oxidation TS.

52 shows that Tl(III) can do decarboxylation in an analogous way when irradiated, and that R. result (evidence includes radical-only rearr of 5-hexenyl to cyclopentylmethyl radical; the C+ would cyclize to the cyclohexyl cation).

58 shows that Co(III) can decarboxylate acids to give R. (rate limiting) and then oxidize the radical, much like is seen with the previous metals.

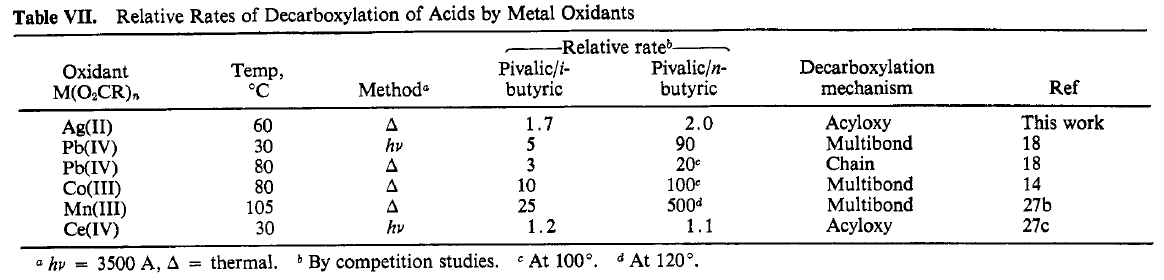

57 does decarboxylation with Ce(IV). Photochemical decarboxylation was largely as expected; thermal is slower but enhanced by strong mineral or Lewis acids. The role of acids is proposed to be protonating and labilizing an acetate, leading to cationic Ce(IV) complex that then is more likely reduced. Alkyl radicals are shown to be intermediates.

71 describes the Ag(I) catalysis of peroxydisulfate decarboxylation of acids. CO2 evolution is first order in both Ag(I) and peroxydisulfate. Ag(II) is proposed to be responsible for decarboxylation, either by HAT or coordination then homolysis of the carboxylate. Cu(II) salts can be added as cocatalysts, unsurprisingly at this point. THe compendium of decarboxylation/alkyl radical generation methods is below: from 71

72 describes the Ag(II) oxidative decarboxylation of acids. The proposed mechanism is carboxylate oxidation to RCO2. and Ag(I), R. then reacts with another Ag(II)

76 Mn(III) acetate does the same too, and is also accelerated by acid. It is inhibited by Mn(II) byproduct.

Chromium(II)

27 demonstrates that Cr(II) can abstract X from R-X (R = benzyl) to give R., which then is reduced by another Cr(II) to give Cr(III) alkyl (and eventually alkane). 35 shows that R. can be generated from acylperoxides, which then continue to be reduced in the same way. The benzylchromium species formed is shown to react further to form toluene (proteolysis/solvolysis) or bibenzyl under different conditions. 36 delineates both pathways and offers mechanisms fo the bibenzyl coupling. Essentially benzyl chromium(III) can react with benzyl halide to couple the two benzyls. This pathway is shown to operate with Co, Hg, V as well. 44 extends this Cr(II) reactivity to simple alkyl halides (tertiary > secondary > primary) by using en/ethanolamine ligands. Alkylchromium species are shown to be intermediates. 79 shows that alkyl radicals have to be involved, and measures rate constants of the R. reassociation to another Cr(II) equivalent.

46 investigates the Cr(II) reduction of vicinal dibromides. The first bromide is removed by Cr(II) abstraction (homolytically), and there is evident NGP by the neighboring bromine substituent. The second halogen is removed by either first-order fragmentation of beta-bromoalkyl radical, or Cr(II) binding followed by trans or cis Cr/Br elimination. (This part of the Kochi program influences the NHK and Takai olefinations). 49 studies the analogous reduction with alpha,gamma-disubstituted alkanes, which leads to cyclopropanes. Cyclization to give larger rings is hard. Tosylates and halides do cyclization; acetoxy, methoxy, hydroxy etc do not (they still get eliminated to alkenes), suggesting there is little anionic character at the Cr(II)-alkyl bond. Iodine can do anchimeric assistance to eject the first iodine atom to Cr(II). 48 studies this in further detail, and expands the scope of such reductive eliminations to epoxides. Cr(II)en is a stronger reductant than Cr(II) due to larger ligand field stabilization by en. beta-bromine and trimethylammonium can achimerically assist in bromine transfer to Cr(II) because of the possibility of forming a bridged radical.

60 studies the stereospecificity of the vic-dihalide elimination; only bromides are stereospecific (and not epoxides, other dihalides, and sometimes episulfides). The proposed explanation is formation of a weak bromine-bridging interaction.

EPR of radicals

56 and 55 describe and apply EPR techniques to observe alkyl radicals. This involves photolysis of a peroxide, generating e.g. an oxy radical that then does HAT on a substrate to generate the observed radical.

66 observes the cyclopropylcarbinyl radical at -150 C for the first time by EPR and shows that it rearranges to allylcarbinyl above -120 C. 65 describes the rearrangement with variously substituted cyclopropanes. Interestingly tetramethylcyclopropane undergoes HAT at the CH3 but is stable to rearrangement. 124 notes that tetramethylcyclopropane is an anomaly and so further substantiates the alkyl radical identities by generating from acyl peroxide.

68 generates Si-centered radicals from Si-H and t-butoxy radical (from peroxide) and measures EPR spectra. When there is a alkoxy substituent on Si, CH abstraction is observed. 62 describes alpha CH abstraction by t-butoxy radical on Group(IV) tetraalkyl compounds. On tetraethyl compounds abstraction of the terminal methyl is also observed; this is due to beta-Si stabilization.

68 observes primary alkyl radicals by EPR. beta-phenethyl radicals do not show aromatic-bridged structures (no hyperfine coupling with aromatic H). 61 shows that trialkylGroup(III) compounds from boron to gallium eject alkyl radicals in the presence of t-butoxy. The proposed mechanism is direct substitution of t-butoxy of R. on the metal, without associative mechanisms (SH2). Trialkylborates undergo HAT on the alpha H of the alkoxy substituent. 63 is the analogous system but with trialkylphosphine. SH2 occurs, but no O transfer is observed. On the other hand, S transfer is exclusively observed if a thiyl radical is used. Phosphites exclusively do O transfer, resulting in t-butyl radical from t-butoxy radical. Triarylphosphite loses aryloxy radical once again by SH2. (antimony and arsenic also work the same way). Nitrogen does not. 100 establishes conclusively the formation of the tetravalent phosphoranyl radicals. CF3 radical is ejected from P(CF3)3. Therefore SH2 occurs on PR3 or P(OR)3 by an addition elimination mechanism.

64 treats cyclobutene or bicyclobutane with t-butoxy radical to give cyclobutenyl radical. It has unusual properties due to the severe angle in the ring. 69 studies the HAT from allenes, finding that the allynyl hydrogen can be abstracted. 78 generates 7-norbornenyl radical and characterizes it. 128 studies the inversion of this radical (the two faces are different; one has olefin). 90 uses EPR to study hindered internal rotation for a beta-sulfur/silicon/germanium/Sn radical; there is a 3d-2p interaction that stabilizes the C.. The Metal group is in the same plane as the long side of the 2p(C) SOMO. 93 concludes that hindered rotatio is due to either hyperconjugation between the pi system and C-M bond, or p-d homoconjugation between pi and metal d orbitals. 111: hf splittings for the metal are unusually large.

97 makes alkylCr(IV) from Cr(OtBu)4 but they generally are not stable.

The neighboring halogen effect is known and can be quite conspiciuous for homolytic reactions; they do EPR studies on this. EPR appears to be a useful tool to study the conformational restrictions of various radicals. 103 characterizes the beta-chloroethyl radical. It has a g factor that is much smaller than alkyl radicals and even of free spin. It also has unusually small hf splittings of the beta protons. 109 expands this to other halogens and various distances. They still fail to observe beta-bromoalkyl radicals. 108: in beta-chloroethyl radical, chlorine sits eclipsed in the plane of the carbon chain, at the node of the radical 2p orbital, either “endo” or “exo”. With butyl radical however the terminal methyl group prefers staggered. 120 by hf and line widths shows that there is bridging by a beta-chlorine atom to a radical. Bridging is associated with restricted rotation about the Ca-Cb bond. 145 shows that Cl migrates from beta to alpha on a radical. 144, 147, adds to these studies.

126 shows that rotation in a .CF2-CH3 radical is restricted. 135 shows that this is due to a pyramidal configuration at the radical site. 134 studies alpha-fluoro radicals but do not have conclusive results. 137 irradiates fluoroketones and observes their decompositiion. Photoexcitred fluoroketones are strong HAT agents.

107 observes alkylsulfinyl (RSO.) and alkylsulfonyl (RSO2.) radicals. 118 generates carboxy radicals (RCO2.) and they add to alkenes. Decarboxylation by CO2 loss is not competitive.

129 photolysis of R3SiO-OCR3 leads to R3SiO. which can do SH2 substitution on the Si of a starting molecule to eject R3COO.

121 abstracts H from methyllithium generating a CH2. that is coupled to three Li nuclei.

143: CF3O-CH2-C2. exhibits bridging (eclipsed conf) behavior by the O. The O does not bridge when there is no electronegative group on it.

156 adds alkoxy radicals to alkenes. 174 adds to allenes

To summarize, two methods are used to determine rotational barriers from EPR. For rotations around Ca-Cb, the temperature dependence of a_beta is fitted to averaging of proton coupling constants. Alternatively, temp dependence of line shapes due to selective broadening is analyzed by density matrix method, modified Block, or relaxation matrix theory.

Cross coupling

151 studies Ni-catalyzed coupling of aryl halides with alkylmetals. (R3P)2NiBr2 promotes coupling of aryl bromides with alkyllithium/grignard. They find arylmethylnickel complexes and propose RE/OA/TM. The observation that oxygen promotes RE of alkylaryl product suggests that there is electron transfer from Ni complex to aryl bromide, which then does rapid RE to Ni+, which then reacts with ArX.- to resume NiArX.

185 shows that Fe and Ni diaryl/dialkyls, upon oxidation, undergo reductive coupling of the two carbon substituents. 190 concludes that Ni(I) undergoes OA to Ni(III), which then TMs an Ar from Ni(II) to make ArAr’Ni(III)X, which does RE. They also identify an arylphosphonium cycle, which is proposed to arise from Ni(II) RE.

Grignard + alkyl halides (Kharasch reaction)

Here comes the triad of papers:

- 89 Ag(I): grignards and alkyl halides couple, catalyzed by Ag(I). This arises from two molecules of Ag-R coupling. One AgR is from Grignard displacing silver halide; the other is from Ag(0) abstracting halide from R. This is a bimolecular process since the rate of coupling rel. disproportionation increases with [Ag].

- 92: Cu(I): argued to be dissimilar to Ag(I). The coupling, in addition, does not involve homolysis. Grignards can also disproportionate with alkyl halide (i.e. make alkene and alkane.)

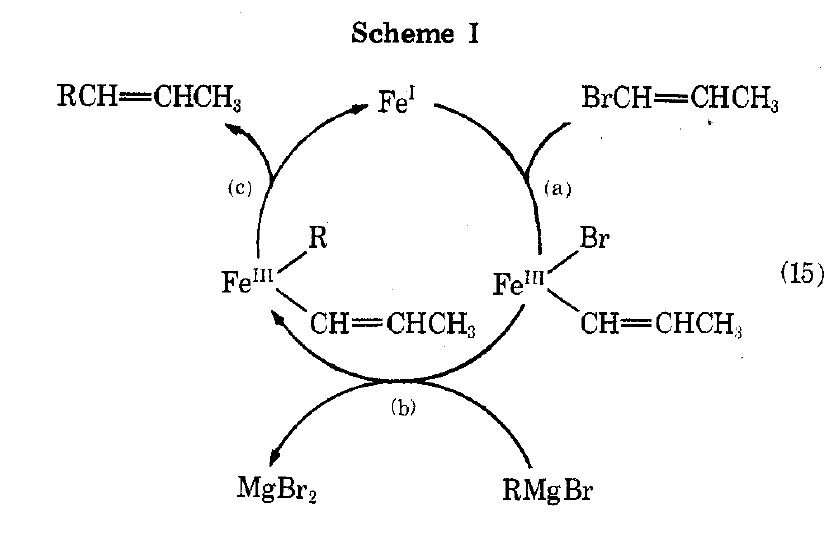

- 82: Fe: mechanistically a combination of Cu and Ag systems; Fe(0) abstracts X from R-X, makes Fe-R. R’MgBr makes Fe-R’. The two combine. 1-alkenyl halides are good for cross-coupling, and they propose the Grignard acts as a nucleophile directly on a Fe-coordinated alkenyl bromide. 152 develops this chemistry to couple alkenyl halides and Grignards. 165 examines alkenyl halide-Grignard coupling and proposes from mechanistic studies OA/TM/RE mechanism starting from Fe(I). The first ever cycle they draw in cycle form, incidentally, is this one:

Disproportionation is observed, and can be explained by BHE/RE. Unlike Ni (151), Fe works at lower loadings and is also stereospecific with no alkyl isomerization.

Disproportionation is observed, and can be explained by BHE/RE. Unlike Ni (151), Fe works at lower loadings and is also stereospecific with no alkyl isomerization.

Generally, there are three mechanistic groups of metals that promote this function: Ag, Cu, and Mn/Co/Ni/Pd/Fe.

80: detailed mechanism for Fe reaction. Note that only the radical from R-X is trappable, therefore R’MgBr that makes R’-Fe does not homolytically dissociate.

84: Studies reaction of Grignard on metal halide salts. The options for reaction from the alkylmetal are: 1. oxidative dimerization; 2. b-hydride elimination, 3. bimolecular disproportionation. (2) and (3) give the same outcome, but the M-H mechanism is more common for Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Pd. Bimolecular is more common for Cu(I) and Ag.

81: Mn(II), or MnCl2, reacts with Grignards to give alkyl MnCl. R2MnCl can result. Alkylmanganese decomposes to alkene, alkane, but not dialkyl. Reduced metals can catalyze the decomposition.

94 adds LiNO3 to Ag-catalyzed Kharasch reaction and finds that nitrate promotes the reaction by oxidizing Ag(0) to Ag(I). Also a mysterious “complex A” that is formed and postulated to be a complex of Ag(0).

99 describes mechanism for the Cu-catalyzed Kharasch. Notably unlike with Ag where R-Ag + R’-Ag couple to R-R’, there is no analogy in Cu. Instead Cu-R attacks R’-X directly (SN2-type) to give the XC product. They also invoke the possibility of ox add to Cu(III).

116 reacts alkylmagnesium with t-butoxy radical and finds alkyl radical and alpha-magnesioalkyl radical (i.e. H abstraction from methyl group).

Somewhat related, 138 studies the reaction of RLi or RMgX with peroxides, showing that the reaction in fact occurs via a single electron pathway. Observations that RLi reactions form R2 and that beta scission products from from the peroxide suggest that the product arises from R. (from alkylmetal) and RO. (from peroxide) in a solvent cage. Accordingly using tertiary alkyl nucleophiles is hard due to the propensity for disproportionation. The radical pair is formed by single e transfer from RLi to peroxide.

Photochemistry

122 irradiates tertiary carbons in acetone, finding that excited state acetone can epimerize tertiary (junction) carbons in ring systems.

Amine Photolysis

91 benzylammonium cations when irradiated at 254 nm afford toluene, bibenzyl, benzyl chloride, benzyl ether, and N-benzylacetamide (with MeCN). Both heterolytic and homolytic pathways are proposed, evidenced by benzyl ethers in alcoholic solvents, and toluene respectively. Quantum yield of toluene formation is insensitive to solvent.

98 photolyzes dibenzylamine, generating benzyl radical and benzylamino radical. These radicals react with each other or abstract H from various species, leading to all the products formed. 95 studies the effect of solvent viscosity on the various pathways. There are various types of “cage effects”: “primary recombination” is before radicals have diffused away more than one molecular diameter (equivalent to thermal relaxation of an excited state); “secondary recombination” is is after they’ve diffused one or two moelcular diameters away.

Arene redox

114 shows that benzene and other electron-poor arenes can be oxidized to cation radical by Co(III) trifluoroacetate then attacked by nucleophile to do oxidative substitution on the aromatic nucleus. Toluene cation radical was observed by EPR. Electron transfer from benzene to Co(III) is rate-limiting. Note differences with Pb(IV), which occurs by two-electron pathway.

117 Tl(III) can be used to one-electron-oxidize arenes to radical cations. Even though Tl(II) is unstable, it disproportionates at the diffusion limit to Tl(I) and (III).

141 argues that the side chain halogenation of arenes is a single-electron process.

Organogold

123 describes the spontaneous isomerization of t-Bu to i-Bu on gold(III), which is proposed to occur by BHE/1,2 addition. 115 R-AuPR3 + R’-Li gives RR’AuPR3 Li. Dialkylaurate(I) can be formed from MePPh3Au(I) and MeLi. This can oxidatively add into alkyl halides to give Au(III). Au(I) alkyls undergo protonolysis, but the selectivity is counter to the usual patterns, suggesting that OA into HCl followed by alkane RE is operative.’ 131 studies the decomposition of trialkylgold(III) complexes, finding that they do reductive coupling rather than disproportionation like is seen with Cu etc. The RE occurs via a dissociative process wherein PR3 leaves before coupling occurs from a trigonal intermediate. 148 shows that the alkylisomerization in 123 also occurs by a dissociative process, whereas cis-trans isomerization is likel a unimolecular inversion of the Au configuration. 164 studies the protonolysis of Au(III) complexes to find that protonolysis occurs by simultaneous H+ transfer/bond breaking. Then dissociation of PR3 promotes RE or dialkyl. 169 studies this theoretically and with isotopic labeling, showing that CH3 and CD3 scramble intermolecularly in nonpolar solvnetsolvent.

177 prepares olefin Au(I) triflate. 179 prepared Au(III). 183 prepares dimethylaurate(I) and tetramethylaurate(III) and studies their decomposition with acid to methane, and with oxygen/MeI to ethane. 182 shows that Au(III) acac ligands can rearrange from O-bound to C-bound. *8181** isolates Me2Au(III)(OTf)

Cu(I)

96 prepares benzene and olefin complexes of Cu(I)(OTf)n. 130 characterizes more of such complexes and measures their NMR spectra to study complexation via exchange. 136 measures the 13C NMR spectra.

112 shows that CuOTf binds olefin and is an efficient photodimerization ([2+2]) catalyst. This gives products different from triplet photosensitizers. 140 examines the photodimerization of norbornene and shows that it arises from a photoexcited (norbornene)2Cu complex. Detailed quantum yield studies are shown. (Burns ladderane synthesis uses this). 146 studies the photodim of cyclohexene, cycloheptene etc. That the unstable stereoisomers are obtained is explained by formation of trans-cycloolefin intermediates that then do allowed thermal cycloaddition.

132 shows that Cu(I) triflate promotes cyclopropanation of olefins. Diazo competes with olefin for Cu coordination; weakly coordinating ligands are essential for high activity. The regioselectivity is also unusual in that less substituted olefins are preferentially cyclopropanated.

Charge transfer

Charge transfer can occur when an electron-rich metal complex encounters an E+, as an alternative to heterolytic nucleophilic attack. 154 shows that R-M can add across olefins. 160 examines charge transfer bands when tetracyanoethylene is mixed with alkylleads, tins, mercuries, finding a formal addition of R-M across the olefin. This arises from single e transfer to TCNE, then transfer of either a radical or cation follows. 189 shows that both photochemical and thermal processes between alkyltin and TCNE can be separately identified and studied. They both involve single electron transfer, then R. ejection and reaction within the solvent cage. 158 examines addition of Grignards to TCNE, finding that charge transfer is involved from Grignard to TCNE.

186 studies addition of trialkylmetal hydrides of Sn, Ge, Si across TCNE, finding that single electron transfer is again common to thermal and photochemical pathways. They can observe the relevant open shell ions in a matrix EPR. They note that the M-H adds, not M-alkyl. This is perhaps important due to charge transfer processes in biology, e.g. to quinones. THey show that charge transfer is more important over H transfer or a radical chain.

Epoxidation

166: Co(III)acac with O2 can epoxidize alkenes. They propose Co(acac)3 decomposes to CO2 and R., which reacts with O2 to give peroxy radical that then adds O atom and generates RO. for propagation.

Organomercury

162 studies the effect of alkyl substituents on the IP of dialkylmercury compounds. 175 shows that hydrogens beta to mercury are activated for HAT. 176 shows that CCl3 radical abstracts H from alkylmercury. R. and Cl. are involved.

171 shows that R2Hg transfer an electron to Ir(IV) or TCNE, generating cation radical that then ejects R. In 180 it an also CT to CCl4, generating CCl3. and R.

Vignettes

When Me radicals are generated by a reducing metal ion from TBHP, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni are all good at promoting dimerization to ethane over methane formation (how?)

17: Cleavage of alkoxy radicals vs HAT is studied. The stability of the ejected alkyl radical is the main determinant of the relative rate, and metal ions do not affect the processes. (This is foundational for Stahl methylation work)

21 reports that photolyzing CuCl2 in the presence of olefins and alcohols etc make them react as if Cl. was generated.

28: benzoyl peroxide and lithium halide lead to molecular halogen and benzoyl hypochlorite. These can do electrophilic halogenation (slower unless there are radical inhibitors) and free radical halogenation respectively, leading to, with toluene as solvent, chlorotoluene or benzyl chloride.

34 measured the dissociation constant for cupric acid.

75 Metal(0) e.g. Pd and Ag promote the decomposition of alkylCu(I). EPR is consistent with the intermediacy of binuclear Cu(I)Cu(0) species.

86 synthesize Co(III) acetate by ozonation of Co(II) acetate. 127 shows that Co(III) trifluoroacetate is a strong one-electron oxidant for alkanes, arenes, and alkenes (e.g. ethylene is oxidized to ethylene glycol di-TFA).

87 isolate Ag(II) complexes of bipy. 85 thiocyanate anion does a displacement of diacyl peroxides at the O-O bond. Another SCN attacks to make (SCN)2.

106: tetraethyllead transfers Et to Cu(I) to give Et3PbOAc and EtCu. The transmettalation is either four-centered or three-centered (linear). 107 describes the ethyllead TM to Cu(II). They favor the alkyl transfer to Cu(II) forming RCu(II)X transiently, which then homolyzes to R. 113 by studying hte relative homolysis propensities of Pb-methyl and Pb-ethyl, provides more support for this mechanism rather than the Pb radical cation mechanism. 125 establishes that the acetolysis of tetraalkyllead may go through a four-member TS to give lead acetate and R-H. Analogies exist to the Cu(I) TM.

119 studies the stereospecificity and mechanism of methyldehydroxylation of alcohols with AlMe3. The mechanism is stereoablative at the alpha carbon, though the carbocation cannot account for all the products.

142 R4Pb can transfer R to Ir(IV). They argue that e transfer occurs from Pb to Ir(IV) before R. is ejected and transfers to another Ir(IV) 155 supports this with radical spin trapping etc experiments.

150 EPR observation of Nb(IV) hydride 159 EPR observation of the anion radical of thiadiazolothiadiazole

161 shows that Grignard can reduce acac to dianion as a Mg chelate.

170 shows that for electrophilic substitution of alkyls attached to Hg, Taft $\sigma *$ is not sufficient, but polarizability is instead important. 173 continues this.

178 shows that in some Pt(allyl) complexes, the allyl binds in a truly sigma fashion, no coordination to the olefin is observed in X ray.

Reviews

47: metal complex redox of alkyl, including Cu and Pb

25a provides a review of the peroxide reduction-oxy radical reaction-alkyl radical oxidation cycle. It also very nicely draws back parallels to the Meerwein/Sandmeyer works.

149: Acc Chem Res on electron transfer mechanisms

163: a chapter on metal-catalyzed oxidations